With only a few elements left, it was time to turn to the shift. Or chemise? Or smock? One of those.

I had left this piece to last since I had not yet decided if I would be stitching the garment entirely by hand or partially by machine. Timing would be key in this decision.

Some background.

Unlike all the silly period movies out there, one would never wear stays or a corset directly against the skin. Structured garments made from expensive material would need a layer of protection from the oils of the skin and general wear and tear so they would last longer and not need to be washed often. Historically, linen was worn against the skin in the form of a smock, shift, chemise, or shirt. Based on my selected time period for the garment (17th century), a chemise would have been the popular term, so that is what we’ll use henceforth.

In regards to our source material (The Goose Girl by Shannon Hale), Izi’s undergarments are mentioned only once when she is riding a horse and playfully chats with another character, Geric, about him possibly seeing her ankle as her “shift” rode up. Since I am taking liberties with the design, the shift in my mind is more tied to the combination of the petticoat and chemise rather than a full length shift that would have been worn if I had selected a medieval tunic design concept.

The Mock Up

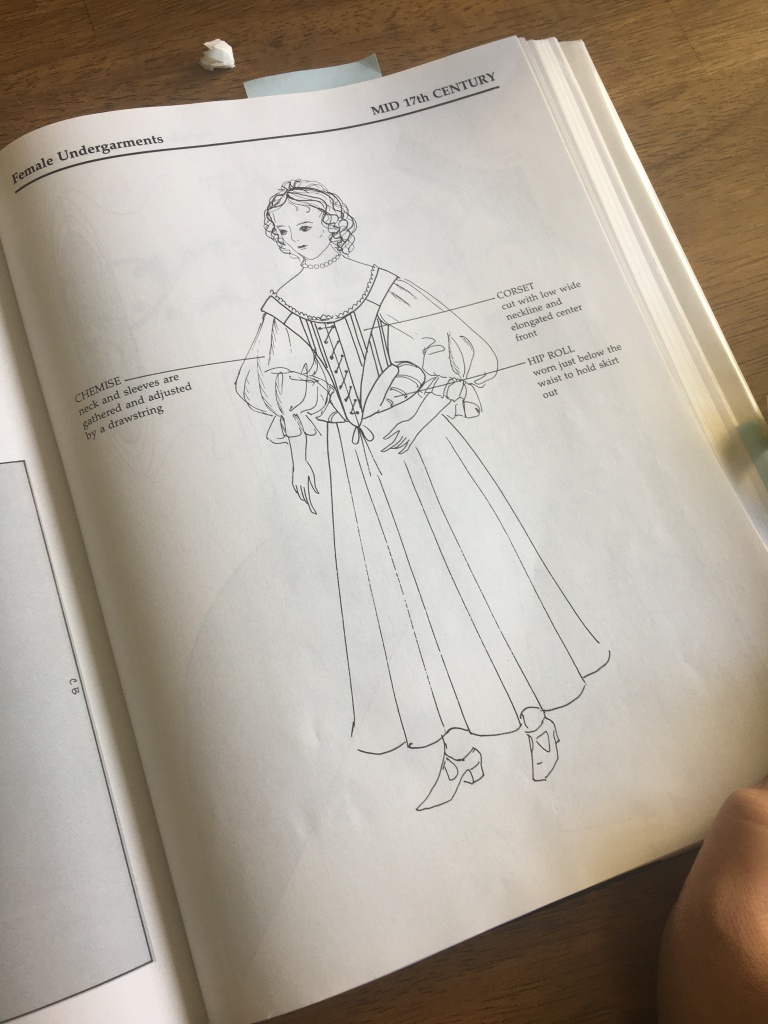

So here we are, with lots of room to play, a simple historical reference, and limited literary bounds. I was torn between two different directions to take the chemise: standard rectangles of a chemise or curved sleeves and neckline from a 17th century pattern I had on hand from Patterns for Theatrical Costumes: Garments, Trims and Accessories Egypt to 1915 by Katherine Strand Holkeboer.

This pattern gave me all the floaty, puff sleeves vibe that I wanted with a nicely curved neckline that would pop under the stays. The pattern here is at ⅛” scale that I would need to transfer and build a mockup to test the fit.

To scale a pattern from a book, you need:

- Tracing paper

- Meter stick (or measuring tape and long straight edge)

- Tape

- Newsprint or large sheets of paper (I reuse packaging paper I get from Chewy deliveries for my spoiled kitties)

- French curve or drafting tools (link to purchase cheap set)

- Scissors

I should preface by saying that this is simply my method for scaling and there are many out there that may work better for you.

To scale a pattern follow these steps:

- Trace original pattern from book and cut out. I recommend labeling what each piece is here already and keep them in a bag, folder, or dish so they don’t get lost. Also be sure to mark any notches or notes to be transferred later.

- Tape tracing pattern piece to corner of larger paper. Ideally, you’ll want to match right angles with right angles if possible to make fitting on the paper easier. In general though, make sure your piece isn’t angled in a way that you’ll run off your page.

- Select a point to measure from for all markings. I always choose a point closest to the right corner of the large paper, again so that you don’t run off your page.

- Measure the distance between this origin point to another point on the pattern (corner, convex/concave of curve, etc.)

- Multiply that measurement by your scaling factor. If the book is at ⅛ scale, you’ll multiply by 8, ¼ scale = x4, ⅙ scale = x6, etc.

- Then, using your meter stick or long straight edge, mark the value from step 5 from the origin point along the EXACT same angle as from the origin to the point on the tracing paper

- Repeat steps 4-6 for as many points as you need to accurately show the shape. My usual markings is to have one point on every corner and a dot for every 1-4” along curves (depending on the tightness of the curve)

- Add markings in a different color pen or symbol for notches, folds, pleats, or other notes from the original pattern.

- Once you have enough points to see the constellation of the pattern, remove the tracing paper piece and begin to connect the dots

- Straight lines are simply connected using your meter stick

- Curves should be connected either free hand if you have enough points and a steady hand, or by using the French curve and curved drafting tools. I try the various curves along at least 3 dots to find the depth of curve that fits best and continue with the various curves, blending between transitions as necessary. This takes a bit of practice and finesse, and lots of reworking to get accurate curves, especially if you don’t have enough dots to start. Err on the side of caution as you start with as many dots as you can tolerate. This also helps eliminate inaccuracy of measurements, math, or transfer. You may have an outlier or two just to the smallest shift in angle or even a 1/16” measurement off. Remeasure and replot these if necessary.

- Once your dots are all connected, you have a full pattern that can be cut and used for a mock up! Transferred patterns like this typically need further size adjustment since they are a single size, so check the description on what standard measurements they are for and adjust initially before cutting mock up fabric.

In following this technique, I drafted, adjusted, and cut a mockup of the chemise from a white microfiber sheet set my kitten had recently ripped.

A general tip: thrift store king sheets are a great, cheap alternative for making mock-ups

I planned to use this mock-up as a PJ dress later, so I chose to be thoughtful about the soft side being toward the body, but this is not necessary for other mockups. Repurposing!

The neckline has a simple hemmed channel that I threaded cotton twill tape through to tighten and gather the neckline when worn. The channel gave a nice soft gather effect I was pleased with and eliminated any need for pattern alterations.

The Final Chemise

A lesson in Returning to the drawing board when fabric patterns get in the way

In selecting my fabric, I hoped to be able to piece together some of the vintage linens I had purchased originally as inspiration for the stays, but these proved to be much too small to ever be enough material. Since I was set on using linen, I went to the local retail fabric store, hoping and praying I’d find something of decent quality so I could get started. I struck out in the linens section as that they were all either too expensive for their lack-luster quality or simply uninspiring. To feel better about the trip, I went to my tried and true clearance section to make sure there was nothing I missed for other project inspiration.

Low and behold, the perfect linen was there, on the spot check clearance shelf.

The pattern reminded me of blackwork embroidery and the contrasting color would add nicely to the design (though, I was a tad nervous about potential clashing of patterned stripes from the stays and a chemise. We’ll cross that bridge later). Plus, it was 100% linen on CLEARANCE. The fabric was meant to be put to this second chance.

I purchased 2 yards to stay in my budget, quickly doing math in my head, and hoping that it was enough. Then, upon getting home, I realized I had made a disastrous error in judgement. I had selected a striped fabric for a curved sleeve pattern.

I physically could have used the fabric with the pattern, but was afraid the stripes would not read as well and the clashing I feared would be more prevalent.

Backtracking, I changed course and decided to use the simple rectangles and squares patterns of a typical 17th century italian chemise for my pattern. Credit goes to Sarah Bendall’s blog post on “Back to Basics: The Smock in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries” for historical context and Jen Thompson of Festive Attyre blog for a starting point on pattern dimensions. For this, I did not draft a pattern, instead opting to use the general measurements Jen T. provided since they were similar to my body already.

To optimize my small 2 yards of fabric (hindsight, not nearly enough as I’d like), with the full gathering effect, the body of the chemise would be more of a shirt length than a full chemise. Since I needed at least 12” for the sleeves to fall at approximately the elbow from the shoulder point, I was left with 60″ between the front and the back panels of the chemise body.

Ensuring I had perfectly straight lines when cutting, I measured the width of my body sections and began the slow, but surprisingly satisfying process of pulling a single thread from the linen.

The thread broke often, but the effect was just so satisfying. I continued with this method for all of my cutting lines for the two body pieces, two sleeves, and two 10” square gussets.

After cutting all my pieces along these thread lines, I also pulled threads ¼” from all sides of the pieces to mark my seam lines so they would be nice and straight.

With all the rectangles ready to go, I started stitching seams using a tiny backstitch since this would take a large amount of strain, especially around the gussets. I stitched the seams in the following order:

- Gusset to side of sleeve seam (x2)

- Gusset and top of sleeve (1” overlap) to body pieces (x2)

- Undersleeve to side body seams, including gussets (fold over along centerline of sleeves and stitch left side to left side and right side to right side)

Overall, the method was to work from the “top” of seams to the “bottom” to allow any inaccuracies to be compensated for in the hems. For example, when stitching the side seams, I started from the end of the sleeve, to the gusset where the line up was precise, to the hem on the body.

Once these seams were completed, I was able to hem the bottom of the body section, sleeves, and neckline using a simple felling method (whip stitch and prick stitch where only one or two of the fashion side fabric is grabbed by the needle so little to no markings are shown on the outside).

Since I had to limit my sleeve length to allow for a decent length for the body panels, I opted to add a cuff to the sleeves that would gather the fullness and create a nice poof around the bicep. I had exactly 16” by 72” of material remaining to use for the cuffs that I thought to experiment with smocking on. I pulled another thread along the 8” width mark to give me two pieces of 8” x 72” pieces that I could smock.

The short edges of the pieces were finished with a tiny rolled hem (~¼”) and whip stitch before folding the 8” length in half, right sides together. Since this seam wouldn’t take heavy strain, I stitched the top with a tight running stitch rather than backstitches.

Once the long seam was stitched, the tubes were turned right side out and pressed to create the base of the cuffs. This was my first attempt at smocking and spent a good amount of time researching and reviewing diagrams on pinterest. In the end, I settled on keeping it simple and doing a modified version of the process detailed in Fortune Favor’s blog.

Ideally, I was planning to achieve a look similar to the dutch blackwork from the period which my fabric thankfully lends itself to.

To smock you’ll need:

- Heavy duty or buttonhole thread for pleating

- Straight edge or cartridge pleat template

- Marking tools (pen, marker, etc)

- Embroidery floss

Rather than reinventing the wheel, I grabbed my cartridge pleat template to mark points for parallel running stitches to be made for the initial pleats. This would make my smocking a bit coarser than the inspiration and sample imagery, but my timeline was getting a bit tight. At the end of the day, I am glad I went with the coarser pleats for the final effect as well as the ease of stitching. More pleats = more lock stitches = more time…

Using my standard method for pleating, I marked my running stitch points using the template and planned on three threads to be strung within the 3 ½” of cuff available. My first length started ½” from the top of the cuff to give a tight pleating at the joint between the upper sleeve and the cuff. The second and third threads were each 1” apart, leaving 1” of material at the bottom of the cuff to create a ruffle.

The threads are pulled tight and tied off to keep the pleats together while doing the embroidery work. I used two strands of navy embroidery floss for speed and to give a tad of emphasis to the stitches. The method I used creates a simple diamond pattern by working from left to right along the diagonal.

Starting at the top row of running stitches at the left, the embroidery floss lock stitches pleat #1 and #2 together with two backstitches. On the third stitch, the thread is sent into the right pleat (#2), down ½”, and out the left side of pleat #2 to start the next stitch. Here, two back stitches lock pleat #2 and #3 together, followed by a third stitch into the right side of pleat #3 and up the channel ½” to be in line with the original stitch between pleat #1 and #2. This zigzag process is continued from left to right through all the pleats.

Once all the pleats have been stitched at ½” and 1” from the top of the cuff, the second row of smocking can be completed. This needs to be offset from the original row or the diamond pattern will not be created.

Once all four rows of lock stitch have been set, you’ll have a checkerboard pattern that when the running stitches are released, will create the diamond pattern. You should have knots of stitching similar to the diagram here:

Mine differs a tad in that I added a 5th row of lock stitches to match with the pattern of the fabric under the stitches which was very pleasing on the right hand side, but not nearly as effective on the left since they were not the same sections of fabric. This 5th row was immensely frustrating since I still needed to follow the zigzag pattern but didn’t want to add excessive stitches to the 4th row of stitches.

With the cuff completed, the smocked section was pinned to the upper sleeve for final stitching. I pinned the “open” section of the smocking to the upper sleeve and left the pleat created by the uppermost lock stitch in the smocking out of the whip stitches. This is similar to how cartridge pleats are applied to a waistband.

With sleeves done and all the other raw edges felled in place or hemmed, the neckline was quickly gathered using a coarse running stitch and buttonhole thread. However, due to the coarse weave and heavyweight of the linen, my threads would either pull out or break nearly every time I attempted to fit test the amount of gathers.

Since I enjoyed the smocking on the sleeves so much, I elected to attempt smocking on the neckline. I removed the remaining gathering threads from the front of the neckline and added two running stitches using the cartridge pleat template and smocked with only three rows of lock stitches using the same method as above.

Upon fit testing the smocking, the natural elastic nature of the smocking was far too loose to create the right fit. This was due to the large pleats I had used in the original running stitches that did not create enough tension. To quickly solve this problem, I cut a piece of cotton twill tape at the correct length needed to cross my chest above the stays neckline, pinned the smocking to the twill tape (easing the bulk into the pleats as I went) and prick stitching the twill tape in place. This locked the correct amount of fullness into the smocking without excessive stretch.

I then used a similar process on the neckline sides and back. I was able to temporarily gather the remaining neckline using the quick thread method and then stitched the gathers in place to cotton twill tape whip stitched on the inside of the neckline. Overall, I felt much better about the security of the neckline under the stays with the application of the twill tape.

The chemise was finally finished! What started as a simple shirt pattern, turned to squares and rectangles, became a MUCH more involved process than I would have imagined, but I am quite pleased with the final product. The shift is simple while having details to allude to the blackwork of the period. Ideally, after this project is done, I would like to line the shift since it is a tad scratchy due to the cheapness of the linen, add a smocked or modern elastic waistband, and wear it as a simple modern summer shirt. Repurposing!

[…] The Goose Girl: Shift, Chemise, Smock….thing […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] The Goose Girl: Shift, Chemise, Smock….thing […]

LikeLiked by 1 person